What are Diffusion Language Models?

Preface

Dear Reader,

I’ve been wanting to write this blog for a long time. Diffusion models for language generation are super exciting — an emerging field that’s getting increasing attention. But up until now, there hasn’t really been a comprehensive guide or intro for folks in the NLP/ML community who want to dive into this area and maybe even start doing research. So here we are! In this blog, we’ll walk through the history of diffusion language models, different paradigms for building them, some future research directions and applications — plus a few of my own (possibly biased) personal opinions, italicized for your reading pleasure. I’ll also keep updating this blog over time, and hey, who knows — maybe it’ll grow into a full survey paper one day.

This blog is mainly for people who already know a decent bit about Diffusion Models and good old autoregressive LLMs. If that’s not you yet, no worries — here are some resources I found super helpful:

- For Diffusion Models:

- What are Diffusion Models? by Lilian Weng (strongly recommended!)

- Understanding Diffusion Models: A Unified Perspective by Calvin Luo

- For Autoregressive LLMs:

- Stanford CS224N (GOAT course, trust me)

What’s a Diffusion Language Model (DLM)?

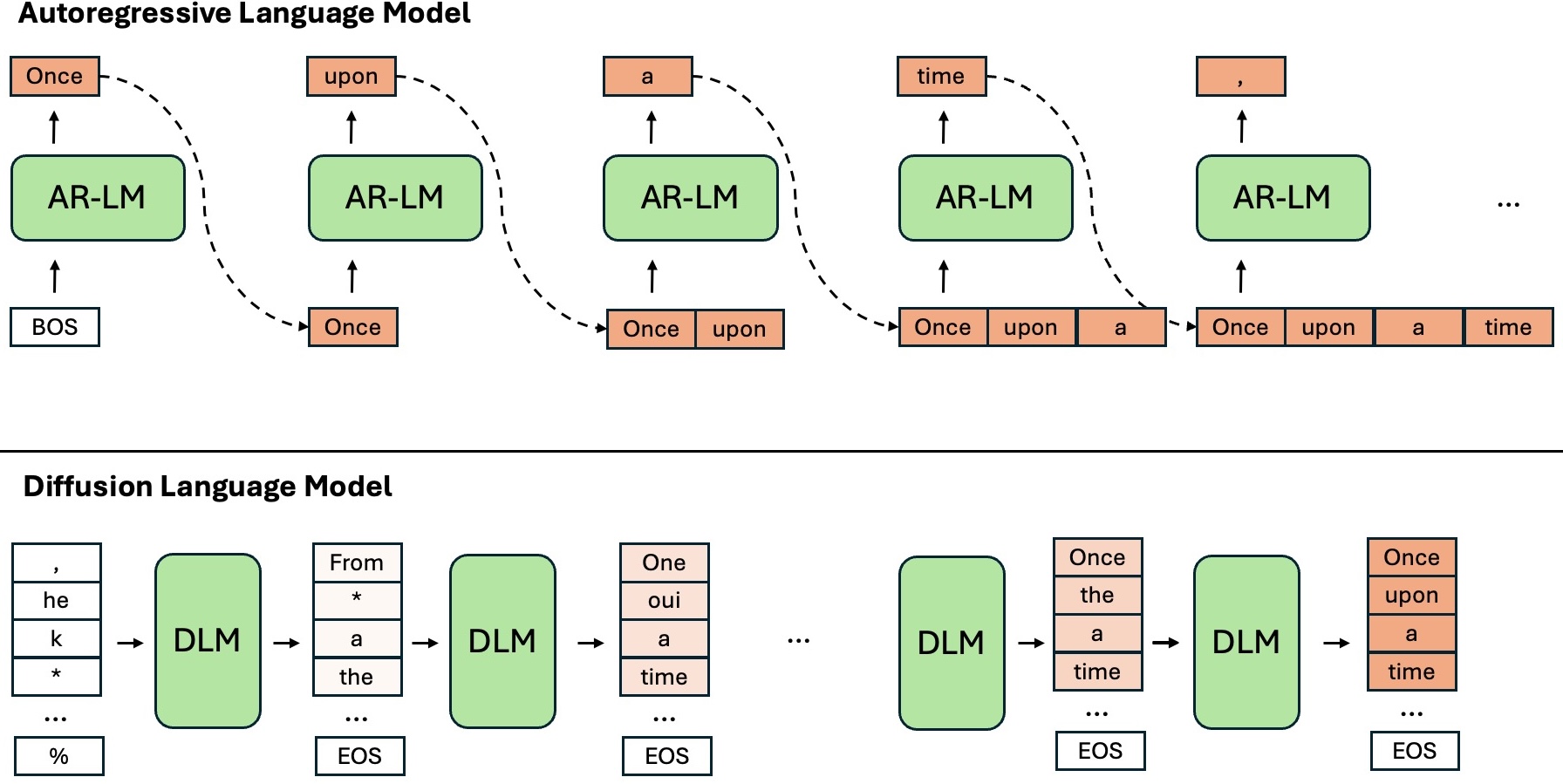

Quick recap: all the trendy autoregressive language models (AR-LMs) these days — GPT-2, Llama, Gemini, ChatGPT, Claude, you name it — use the Transformer backbone for autoregressive (AR) decoding. That means they predict one token at a time, left-to-right.

Diffusion Language Models (DLMs), on the other hand, work differently. Instead of going token by token, they iteratively refine and predict the whole sequence from a noisy starting point — following a non-autoregressive (NAR) decoding process.

Here’s a (very simplified) way to picture the difference between the two paradigms, shown in the figure below:

Putting it in mathematical terms: Suppose we want to predict a sequence \(\mathbf{x} = \{x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_N\}.\) An AR-LM (autoregressive language model) with parameters \(\theta\) models the following distribution:

\[\begin{equation} \label{eq:AR-LM} P(\mathbf{x}; \theta) = \prod_{n=1}^{N} P(x_n \mid \mathbf{x}_{<n}; \theta) \end{equation}\]In contrast, DLMs take a holistic view of the entire sequence. They model a different kind of distribution — one that evolves over time \(t\) in a reverse diffusion process (don’t worry, we’ll get into the details very soon). Here, a larger \(t\) corresponds to a noisier version of the sequence — something closer to random Gaussian noise.

You can think of it like we start with a super messy paragraph and then iteratively CLEAN it up until it becomes the polished passage we actually want.

Why do we need DLMs (or NAR)? What’s wrong with AR?

Autoregressive models are insanely successful these days — so why bother with another paradigm? Why is DLM a field worth looking into? Well, here are some arguments for you to consider:

- Inherent Disadvantages of AR-LMs

-

Error Propagation:

In autoregressive models, if you make a mistake when predicting the current token, tough luck — you can’t go back and fix it. Future predictions are based on that flawed token, causing errors to propagate and accumulate over time. This painful phenomenon is known as error propagation. -

Indirect Generation Control:

Controlling AR generation is tricky. Most methods rely on heavy training or hacks during decoding — and honestly, they’re pretty inconvenient. For example, if you want to generate a passage of a certain length, you either have to train a separate length predictor or do fancy prompting. Other controls may rely on heuristics like top-k sampling. And even then… there’s no guarantee it’ll work 😥. -

Computational Constraints:

Token-by-token generation is slow because the model must wait for previous tokens to be fully decoded before predicting the next ones. Plus, the strict left-to-right setup limits tasks that require reverse reasoning — a problem known as the “Reversal Curse”.

-

- (Potential) Advantages of DLMs

-

Non-Autoregressive (NAR) Generation:

Since sequences are generated holistically, the model can fix earlier mistakes as it refines the output — no more getting stuck with bad early guesses. -

Controllability:

Diffusion models are naturally good at controllable generation! Using tricks like classifier-free guidance or classifier-based guidance (Prafulla et al., 2021, Radford et al., 2021), we can easily steer the output style. In DLMs, this can extend even further — allowing fine-grained control over length, specific text edits, infillings, and structural constraints like code and tables (Li et al., 2022, Nie et al., 2025). -

Diversity:

Want different outputs? Just sample different initial noise — no fancy beam search or sampling needed 🎲. -

(Potential) Speed Up:

Since generation doesn’t have to happen strictly token-by-token, there’s potential for faster, more parallelized decoding.

-

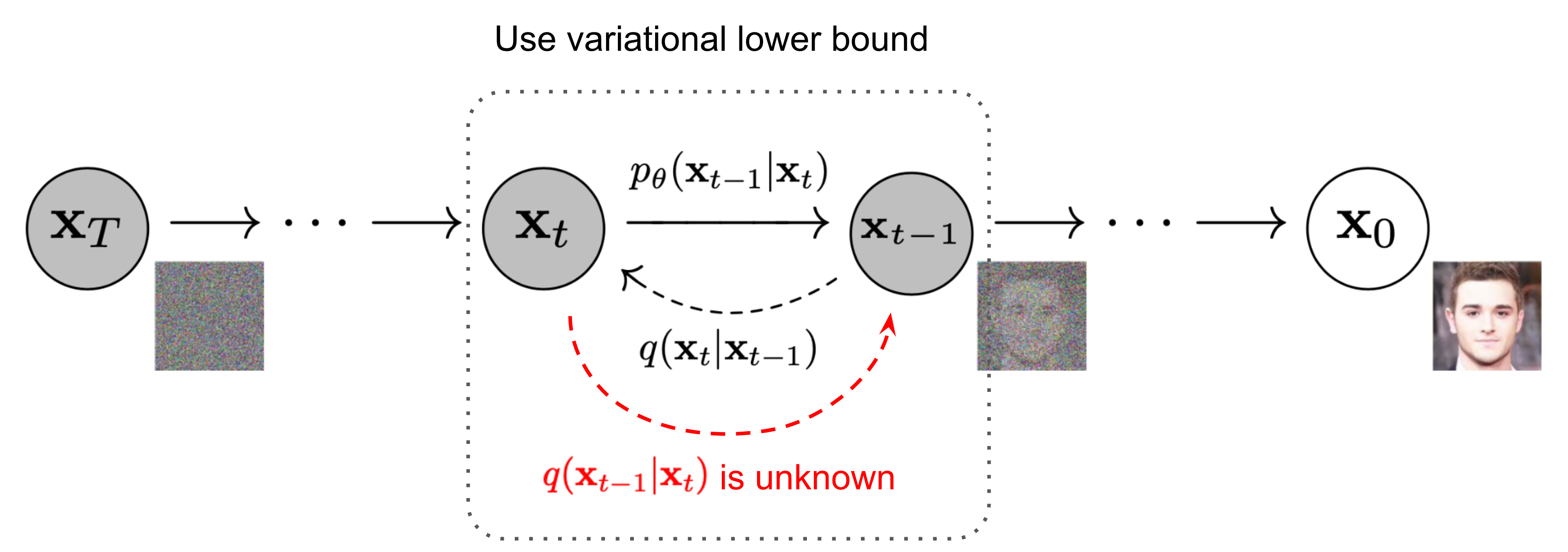

Diffusion Model Recap

Diffusion models are very successful and widely adopted in computer vision tasks, such as image generation, super-resolution, and inpainting. The core idea of diffusion models is to learn a generative model by reversing a diffusion process that gradually adds noise to the data. Using the famous DDPM as an example, given a data sample from a real data distribution \(\mathbf{x}_0 \sim \mathcal{D}(x)\), we use a forward process to gradually perturb the data with small amounts of Gaussian noise over \(T\) steps:

\(\begin{equation} q(\mathbf{x}_t | \mathbf{x}_{t-1}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{x}_t; \sqrt{1 - \beta_t} \mathbf{x}_{t-1}, \beta_t \mathbf{I}) \end{equation}\) \(\begin{equation} q(\mathbf{x}_{1:T} | \mathbf{x}_0) = \prod_{t=1}^T q(\mathbf{x}_t | \mathbf{x}_{t-1}) \end{equation}\)

where \(\beta_t \in (0, 1)\) is a variance schedule that controls the amount of noise added at each step. As \(T \to \infty\), \(\mathbf{x}_T\) approaches a sample from a standard Gaussian distribution:

\[\begin{equation} \lim_{T \to \infty} \mathbf{x}_T \approx \mathcal{N}(0, \mathbf{I}) \end{equation}\]The reverse process then learns to gradually denoise the data, starting from pure noise \(\mathbf{x}_T \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \mathbf{I})\) and working backwards, where \(\mu_\theta\) and \(\Sigma_\theta\) are learned by a fancy neural network model. Again, if you are not comfortable with these concepts, please refer to Lilian’s amazing blog.

\[\begin{equation} p_\theta(\mathbf{x}_{0:T}) = p(\mathbf{x}_T) \prod_{t=1}^T p_\theta(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} | \mathbf{x}_t) \end{equation}\] \[\begin{equation} p_\theta(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} | \mathbf{x}_t) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{x}_{t-1}; \mu_\theta(\mathbf{x}_t, t), \Sigma_\theta(\mathbf{x}_t, t)) \end{equation}\]

What’s the Fundamental Challenge?

Well, if Diffusion Models are so well-established and come with all these exciting perks, why aren’t they as trending in NLP as they are in computer vision? 👀

Good question — and now we get to the fundamental challenge: there’s a big discrepancy between traditional continuous diffusion models (which crushed it in image generation — see Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models, Ho et al., 2020) and the world of discrete text.

Think about an image: it’s made of pixels, and each pixel has color values (like RGB) — basically numbers on a continuous scale. Adding “noise” is super intuitive: you just perturb those numbers a little, typically by adding random Gaussian noise. Gradually adding more and more noise smoothly transitions the image into random static. And the reverse process? Just train a model to predict and subtract that noise step-by-step, and voilà — the original image comes back.

Now, consider text: language is made of discrete units — words or tokens picked from a finite vocabulary (“cat”, “dog”, “runs”, etc.). You can’t just add “0.1 Gaussian noise” to the word “cat” and expect to get something slightly fuzzier but still meaningful. Applying the same continuous noise idea directly just doesn’t work.

This discrete nature of text is the core hurdle. The big question is:

How do you define a “forward process” that gradually corrupts text into noise — and, critically, a “reverse process” that a model can learn to invert, step-by-step?

Researchers have developed some clever workarounds to bridge this gap:

Operating on Continuous Variables

One approach is to not work with the words themselves, but with their embeddings, which are continuous. Traditional language models already produce well-constructed word embeddings and hidden layer outputs. We can leverage these representations to define a continuous forward process, where the model learns to predict the noise added to these continuous vectors at each step. This is similar to how diffusion models operate in the image domain — often working in the latent space of a VAE or similar architecture.

-

Word Embedding (Token Level):

Noise can be added to word embedding vectors — a technique used in models like Diffusion-LM and the pre-trained DLM GENIE. However, mapping potentially noisy embeddings back to specific discrete tokens at each step introduces its own complexities. -

Higher-Level Latent Representations:

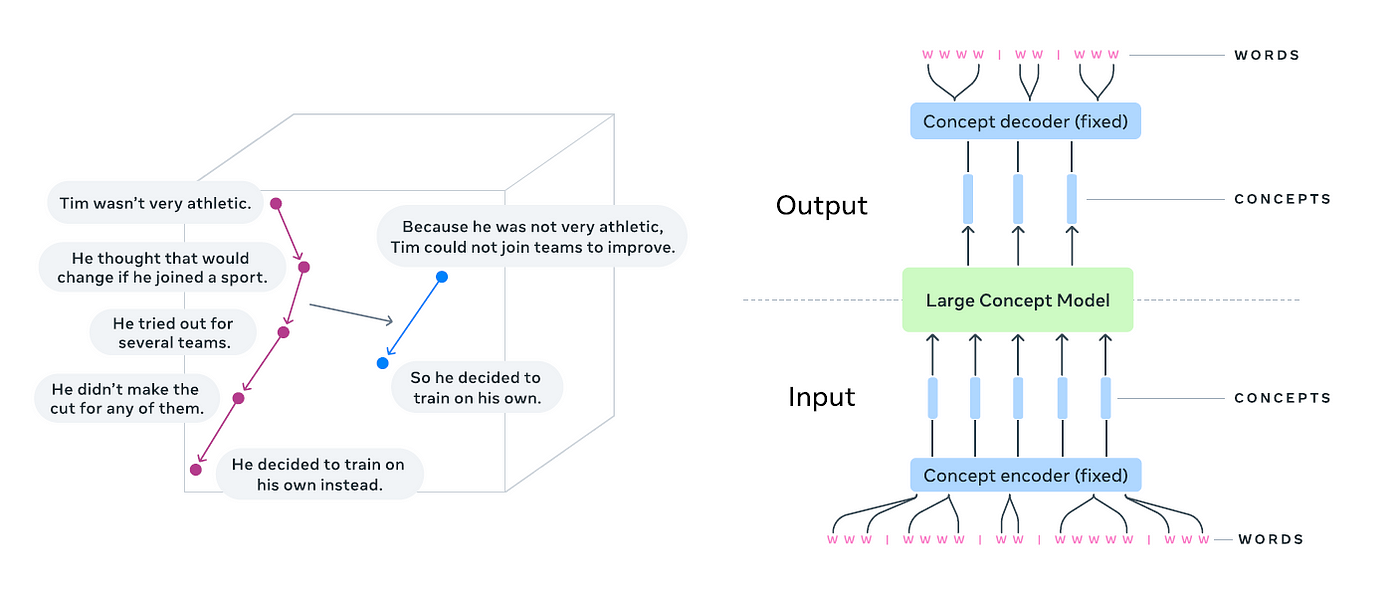

Works like PLANNER and LD4LG operate on latent representations of paragraphs of text. But these representations can be pretty fragile — even small noise can cause abrupt semantic shifts during reverse diffusion. My own paper SLD tackles this problem cleverly by introducing text-segmentation and improved representation learning techniques. Also worth checking out: Meta’s Large Concept Model, the existing pre-trained DLMs following this path.

Discrete Diffusion over Tokens

Some bold geniuses thought: “Hey, if tokens are discrete, why not make the diffusion process discrete too?”

And so — we now have discrete diffusion over categorical supports. Eminel et al., 2021 extended diffusion to handle categorical data like text. Here, each token is represented as a probability mass vector over the vocabulary \(p \in \mathbb{R}^{V}\), where \(V\) is the vocabulary size. We use transition matrices \(\mathbf{Q}\) to model token-level transitions over timesteps, e.g.,

\[q(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_{t-1}) = \text{Categorical}(\mathbf{x}_t; \mathbf{p} = \mathbf{x}_{t-1}\mathbf{Q}_t)\]Models like D3PM and SEDD (ICML 2024 Best Paper 🏆) follow this path. More commonly, text diffusion models define analogous discrete “noising” or “corruption” processes. Instead of adding mathematical noise, the forward process might involve:

-

Masking:

Randomly replacing tokens with a special[MASK]token, with the amount of masking increasing over diffusion steps.

(Example: LLaDA — an 8B-parameter pre-trained DLM that’s currently trending.) -

Token Substitution:

Randomly replacing tokens with other tokens from the vocabulary. (Check out Zou et al., 2023) -

Hybrids:

Combining masking, substitution, and other discrete corruption methods. (Check out Yang et al., 2024)

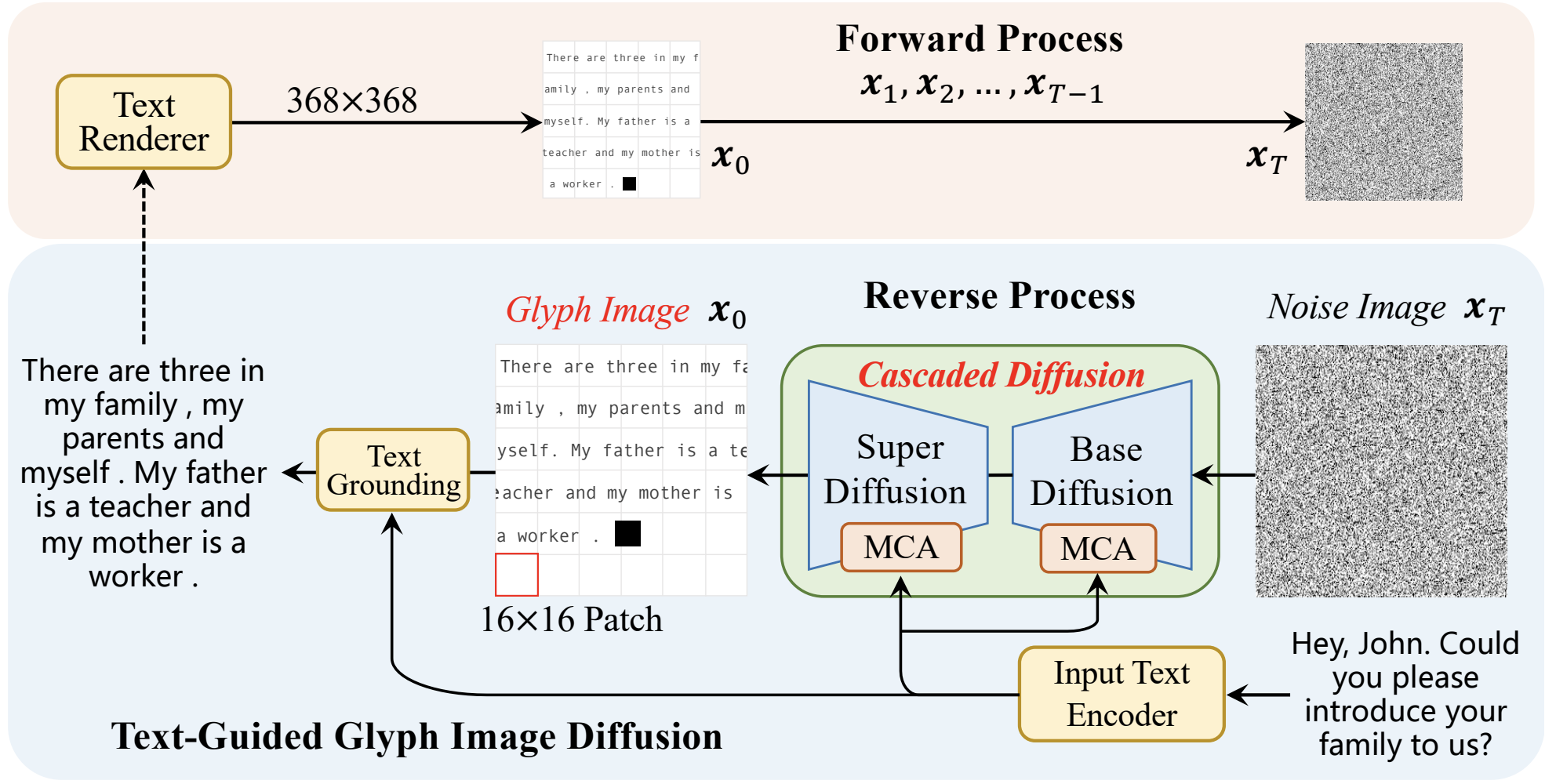

🔥🖼️👊 The Maverick — Text as Image

“Discrete text? What text? It’s an image!” 🤣

Instead of dealing with the discrete gap, GlyphDiffusion bypasses it entirely — by rendering the target text as glyph images containing visual language content. (Yes, seriously. I like the idea very much. I personally wish you to check this out.)

In all these methods, the reverse process becomes about undoing specific types of corruption. For instance, the model learns to predict the original tokens at [MASK] positions, or correct randomly substituted tokens, gradually refining the sequence from a highly corrupted mess back into coherent text. So while the core idea of diffusion (iterative refinement from noise) stays the same, the mechanisms for forward (corruption) and reverse (denoising) processes have to be carefully adapted for the discrete world of language.

Now, I’ll pick representative works from each paradigm to explain DLMs in more detail. For each paradigm, I’ll introduce key papers, explain the mechanisms, and point you to off-the-shelf pre-trained models you can try out yourself!

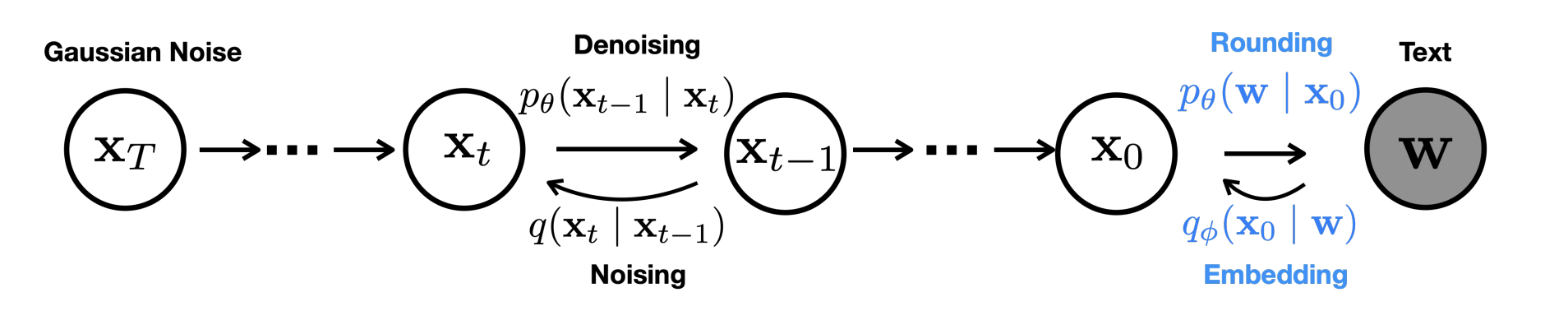

Embedding-Level Diffusion — Where It Begins

1. Token-Level Embeddings

As far as I know, Diffusion-LM is probably the first influential work that kicked off the DLM era 🎉. Suppose we have a sequence of words: \(\mathbf{w} = \{w_1, w_2, \ldots, w_n\}\) An embedding function maps each word into a vector: \(Emb(w_i) \in \mathbb{R}^d\) Thus, the entire sequence is encoded into: \(\mathbf{x}_0 = Emb(\mathbf{w}) \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times d}\)

Awesome! Now we have a continuous space where we can run good old conventional diffusion models.

(We use the typical simplified KL-divergence term from the evidence lower bound — which I won’t rehash here — to derive the loss.)

Specifically, the training objective is:

\[\begin{equation} \mathcal{L}_{simple}(\mathbf{x}_0, \theta) = \sum_{t=1}^T \underset{q(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_0)}{\mathbb{E}} \left[ \|\mu_{\theta}(\mathbf{x}_t, t) - \hat{\mu}(\mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{x}_0)\|^2 \right], \end{equation}\]where \(\hat{\mu}(\mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{x}_0)\) is the closed from Gaussian, the noised variable in the forward process. \(\mu_{\theta}(\mathbf{x}_t, t)\) is the predicted mean, computed by our trainable neural network, which is the diffusion model. But hold on — we can’t forget about converting embeddings back into discrete tokens! You might think: “Easy, let’s just use another function to transform them back.” And… you’d be mostly right. In Li’s implementation, they model these steps into the diffusion process as an extra timestep. As shown in the figure below (👀), the forward process includes an additional Markov transition to obtain embeddings:

\[q_{\phi}(\mathbf{x}_0 \mid \mathbf{w}) = \mathcal{N}(Emb(\mathbf{w}); \sigma_0^2 I)\]Then, in the reverse process, you have an additional trainable rounding step, parameterized by:

\[p_{\theta}(\mathbf{w} \mid \mathbf{x}_0) = \prod_{i=1}^n p_{\theta}(w_i \mid x_i)\]where each \(p_{\theta}(w_i \mid x_i)\) is a simple softmax distribution over the vocabulary.

Then we can adjust the loss function accordingly. For end-to-end training, we arrive at the final loss function shown below. During inference (i.e., the reverse process), you sample a random embedding sequence containing \(n\) token embeddings — same as during training — and gradually remove the noise, step by step. You’re always predicting all \(n\) embeddings together, since the diffusion model expects fixed-shape inputs and outputs. (Kind of wasteful if your sequence is shorter than \(n\), right? We’ll talk about that later.)

\[\begin{equation} \mathcal{L}_{simple}^{e2e}(\mathbf{w}, \theta) = \underset{q_{\phi}(\mathbf{x}_{0:T} | \mathbf{w})}{\mathbb{E}} \left[\underbrace{\mathcal{L}_{simple}(\mathbf{x}_0)}_{\text{diffusion Loss}} + ||Emb(\mathbf{w}) - \overbrace{\mu_{\theta}(\mathbf{x}_1, 1)}^{\text{predicted }\mathbf{x}_0}||^2 - \underbrace{\log p_{\theta}(\mathbf{w} | \mathbf{x}_0)}_{\text{rounding}} \right] \end{equation}\]So, everything seems super straightforward, right? Or… does it? Unfortunately, no 😅. The conversion between continuous embedding space and discrete tokens is actually non-trivial — and harder than you might think. This rounding step is a key challenge in token embedding-level diffusion models. Discretization can introduce errors that accumulate across the diffusion process, since the embedding space isn’t uniformly filled with valid tokens. Well, isn’t this just the notorious data sparsity problem making a comeback?

In the paper, there’s a whole section dedicated to techniques for reducing rounding error and producing better outputs. For instance:

- They use the reparameterization trick to ensure every term in the loss explicitly models \(\mathbf{x}_0\).

- They also introduce a clamping trick, which maps each predicted vector \(\mathbf{x}_t\) to its nearest word embedding in every reverse sampling step.

Still, a lot of work remains to be done here if we want to really boost generation quality.

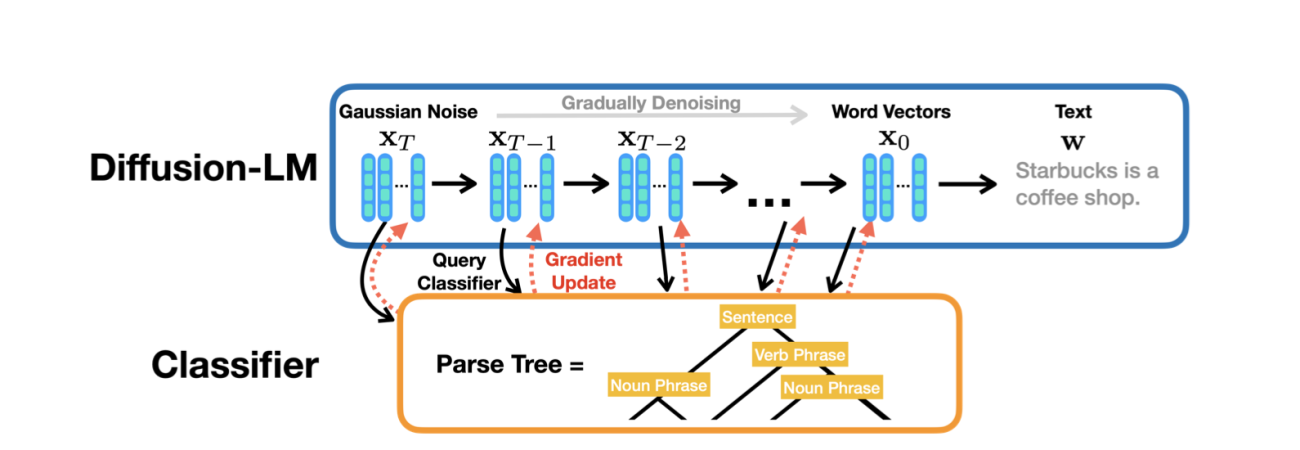

Back to the model itself, with the diffusion pipeline, you can do the fancy conditioning and controlled generation during your inference now. For example, you could have a separate neural network classifier and a class condition \(\mathbf{c}\). During the backward process, you obtain the \(\mathbf{x}_{t-1}\) with respect to the posterior probability using the gradient update below.

\[\begin{equation} \nabla_{\mathbf{x}_{t-1}} \log p(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} | \mathbf{x}_{t}, \mathbf{c}) = \nabla_{\mathbf{x}_{t-1}} \log p(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} | \mathbf{x}_{t}) + \underbrace{\nabla_{\mathbf{x}_{t-1}} \log p(\mathbf{c} | \mathbf{x}_{t-1})}_{\text{classifier guidance}} \end{equation}\]

The table below gives a demonstration of how Diffusion-LM outperforms traditional controlled generation paradigm (FUDGE, Fine-tuning) in review generation. The paper also provides a bunch of experiments on controlled generation — including syntax tree, length, part-of-speech, and more.

| target semantic content | name : Travellers Rest Beefeater |

|---|---|

| FUDGE | Clowns near Clare Hall in riverside is a French coffee shop rated 5 out of 5 |

| Diffusion-LM | Green Man is an Italian pub located in the city centre near Café UNK. |

| FT | Travellers Rest Beefeater is a reasonably priced restaurant that is family friendly. |

But I want to highlight infilling specifically, because it’s super neat. 🧩 In this setting, during inference, instead of denoising all embeddings, some context embeddings are given and fixed. For example: \(\mathbf{x}_t =\) [w_1] [MASK] [w_2]. The diffusion model is told to only generate the noisy token in the middle. This is done by masking the gradients of the fixed tokens — so they stay untouched — while still using them as context during the reverse sampling process. In other words, the fixed tokens act as classifier-free guidance. And you, my clever reader, have probably already realized: this setup makes it easy to model traditional sequence-to-sequence tasks — just give the input as the left context!

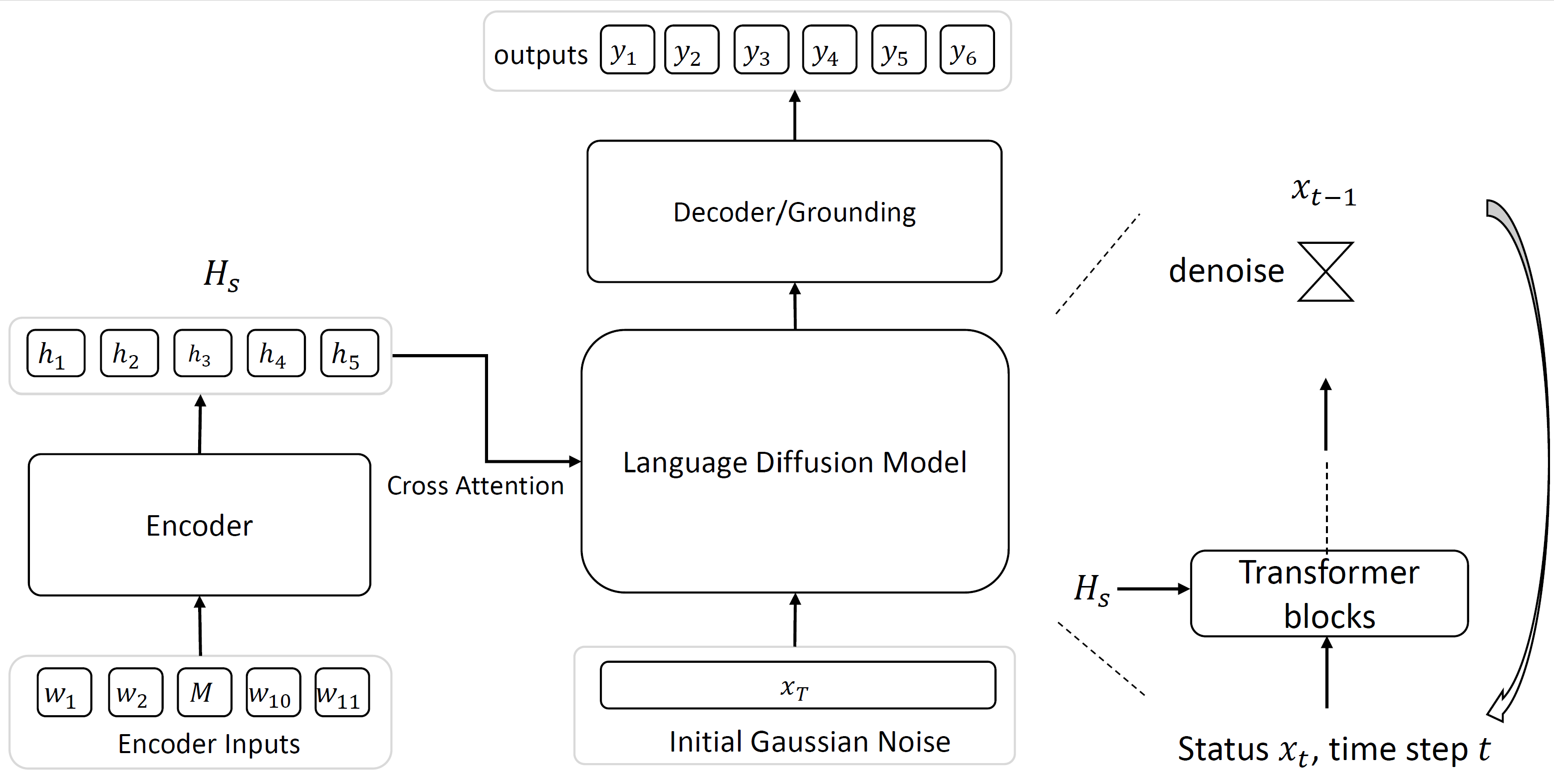

GENIE is (again, as far as I know) the first pre-trained DLM to follow this token embedding-level diffusion path. It uses a continuous paragraph denoising objective for pretraining.

The idea:

- Apply a hybrid noising process to the original text — including token masking (like

[w_1] [MASK] [w_2]) and forward diffusion sampling. - Then train the model to recover the clean original text from the noisy version.

Notably, GENIE doesn’t use infilling as its default sequence-to-sequence generation method. Instead, it follows more of an Encoder-Decoder approach (yep, think BART or T5) — which is actually another form of classifier-free guidance. The input is fed to the diffusion model, a transformer in this case, as cross-attention targets. The equation below covers the key training step. They use a cross-attention transformer \(z_{\theta}\) to predict the mean of word-embeddings for the next timestep. \(\mathbf{H}_s = \{\mathbf{h}_1, \mathbf{h}_2, \ldots, \mathbf{h}_n\}\) is the encoder output of the \(n\)-token long input, as the guidance.

\[\begin{equation} \mu_{\theta}^{t-1} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\alpha_t}} \Biggl( \mathbf{x_t} \;-\; \frac{\beta_t}{\sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t}}\, z_{\theta}(\mathbf{x_t}, t, \mathbf{H}_s) \Biggr) \end{equation}\]GENIE’s inference process is the same as Li’s work. Similar rounding techniques are applied here too: GENIE uses an efficient KNN (k-nearest neighbors) algorithm to retrieve the closest word embedding for each token during reverse sampling, then rounds to the nearest learned word embedding. This rounding step helps map noisy continuous vectors back to valid discrete tokens more effectively — though, as always, there’s still room for improvement!

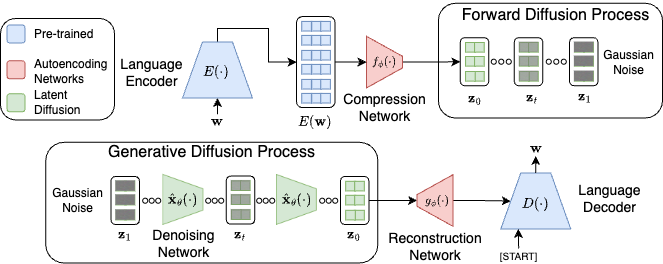

2. Higher-Level Embeddings

To address the rounding error problem when translating predicted word embeddings back to discrete tokens, researchers have explored bringing diffusion into a higher-level semantic latent space — like at the sentence or paragraph level. In this setup, the diffusion model doesn’t operate directly on word embeddings. Instead, it predicts a latent representation of an entire piece of text. Then, a separate autoregressive decoder is used to decode that latent into natural language. So the rounding is bypassed as we are not handling discrete text during the diffusion process. One representative example is the work by Lovelace et al., Latent Diffusion for Language Generation (LD4LG). We’ll use this to walk through how the concept works.

First, an encoder model (e.g., BART or T5 Encoder), denoted as \(Enc()\), is used to convert a piece of text \(\mathbf{w} = \{w_1, \ldots, w_n\}\) into hidden states: \(Enc(\mathbf{w}) \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times h_{lm}}\) where \(h_{lm}\) is the hidden size of the encoder (typically 768 or 1024, etc.).

Notice that \(n\) here represents the variable token length of the text, but diffusion models usually require a fixed-shape representation. In token-level embedding diffusion, this imposes a hard constraint on the context window size. For higher-level embeddings, we use an additional pooling/compression unit \(f()\) to project the hidden states into a fixed-length latent: \(\mathbf{z} = f(Enc(\mathbf{w})) \in \mathbb{R}^{k \times h_{rep}}\) where \(k\) and \(h_{rep}\) are hyperparameters defining the shape of the latent space. Typically, you want \(k < n\) and \(h_{rep} \ll h_{lm}\) — because you don’t want a sparse, oversized latent. A more compact latent space helps the diffusion model learn the distribution more effectively.

Then, the diffusion model \(R(\cdot \mid \theta)\) (usually a diffusion transformer, like DiT), is deployed to learn how to recover \(\mathbf{z}_0\) from its noised version \(\mathbf{z}_t\) over the forward diffusion process — as usual.

\[\begin{equation} \mathcal{L}(\theta_{R}) = \sum_{t=1}^T \underset{q(\mathbf{z}_{t} | \mathbf{z}_0)} {\mathbb{E}} \left\| \hat{\mathbf{z}}_{t} - \mathbf{z}_t \right\|^2_2 \end{equation}\]For inference, you start by sampling a latent representation from Gaussian noise, then run the reverse process as usual \(\hat{\mathbf{z}}_{t-1} = R(\hat{\mathbf{z}}_t, t; \theta_R)\) Conditioning (e.g., class labels, prompts) can also be added to both the forward and reverse processes — just like in other diffusion models. Next, we apply a reconstruction unit \(g()\) to project the denoised latent state back into the hidden dimension of the decoder LM. Then, the decoder generates text as follows: \(Dec(g(\mathbf{z}_0))\) Since we’re doing diffusion over the continuous latent space of high-level semantics, we effectively bypass the whole rounding phase from token-level embedding models.

BUT, is it that simple? Actually… no ☹️. It’s non-trivial to find a good latent representation for text — let alone generate one from noisy examples. For example, take the sentence: "It is sunny today" Now, if I perturb its latent representation just a bit, what should that mean? Well, this is semantic diffusion, right? So a small change should preserve the meaning, not just the surface form. We’d hope to get something like: "Today is sunny" or "Today has sun" Not: "It isn't sunny today" or "It is savvy tody" 🙃 The latter examples may look similar in terms of characters or token embeddings, but they’re clearly not semantically close.

And that’s the crux of the problem: the meaning of even a short paragraph is super rich and subtle. How are we supposed to regularize a latent space that captures that? This poses a major challenge for high-level semantic diffusion — especially when it comes to long-form generation, as it usually packs more and complex meanings.

So… back to square one: What’s the definition of a good latent representation for high-level semantic diffusion? Zhang et al., 2024 gives a formal definition of this, describing three key desiderata:

1. Low Conversion Error

Given a piece of text \(\mathbf{w}\), we encode it into latent representations and decode it back: \(\tilde{\mathbf{w}} = Dec(g(f(Enc(\mathbf{w}))))\) The difference between the original \(\mathbf{w}\) and the reconstructed \(\tilde{\mathbf{w}}\) should be minimal — ideally none. However, this is hard when \(\mathbf{w}\) is long. Remember, \(k\) and \(h_{rep}\) are fixed hyperparameters. So during projection, information gets compressed — and longer sequences suffer more loss. (Makes sense, right? The longer the sequence, the more stuff you have to cram into a fixed-size box! 📦)

2. Local Smoothness

Imagine someone stuttering or dropping a few minor words while speaking — you can usually still understand them. Similarly, given a piece of text \(\mathbf{w}\) and a slightly varied version \(\mathbf{w'}\), their encoded latent representations should be close to each other: \(\mathbf{z}_{w} \approx \mathbf{z}_{w'}\) This ensures the latent space is locally smooth, tolerant to small, surface-level changes without drastic semantic shifts.

3. Distributional Smoothness

In the high-level latent space, we want meanings of paragraphs to be smoothly distributed. That is:

- A piece of text \(\mathbf{w}\) and its paraphrases should have nearby latent vectors.

- Small perturbations in latent space should preserve meaning.

- Texts with very different meanings should be far apart in latent space.

Sounds good — but super hard in practice, especially for long-form text! Longer sequences carry multiple complex ideas, making the latent space messy and harder to regularize. If you increase the size of the latent space to capture all that complexity, the diffusion model faces another challenge: learning a distribution \(p(\mathbf{z})\) that is highly multimodal or has a large Lipschitz constant — meaning the density function can change very abruptly, which is nasty for diffusion models to handle.

So the truth is: without proper regularization, the learned latent distribution can become fragile — small perturbations might cause abrupt semantic shifts, making life hard for the diffusion model and catastrophically corrupting the quality of the decoded text. Yikes.

So… how do we fix this?

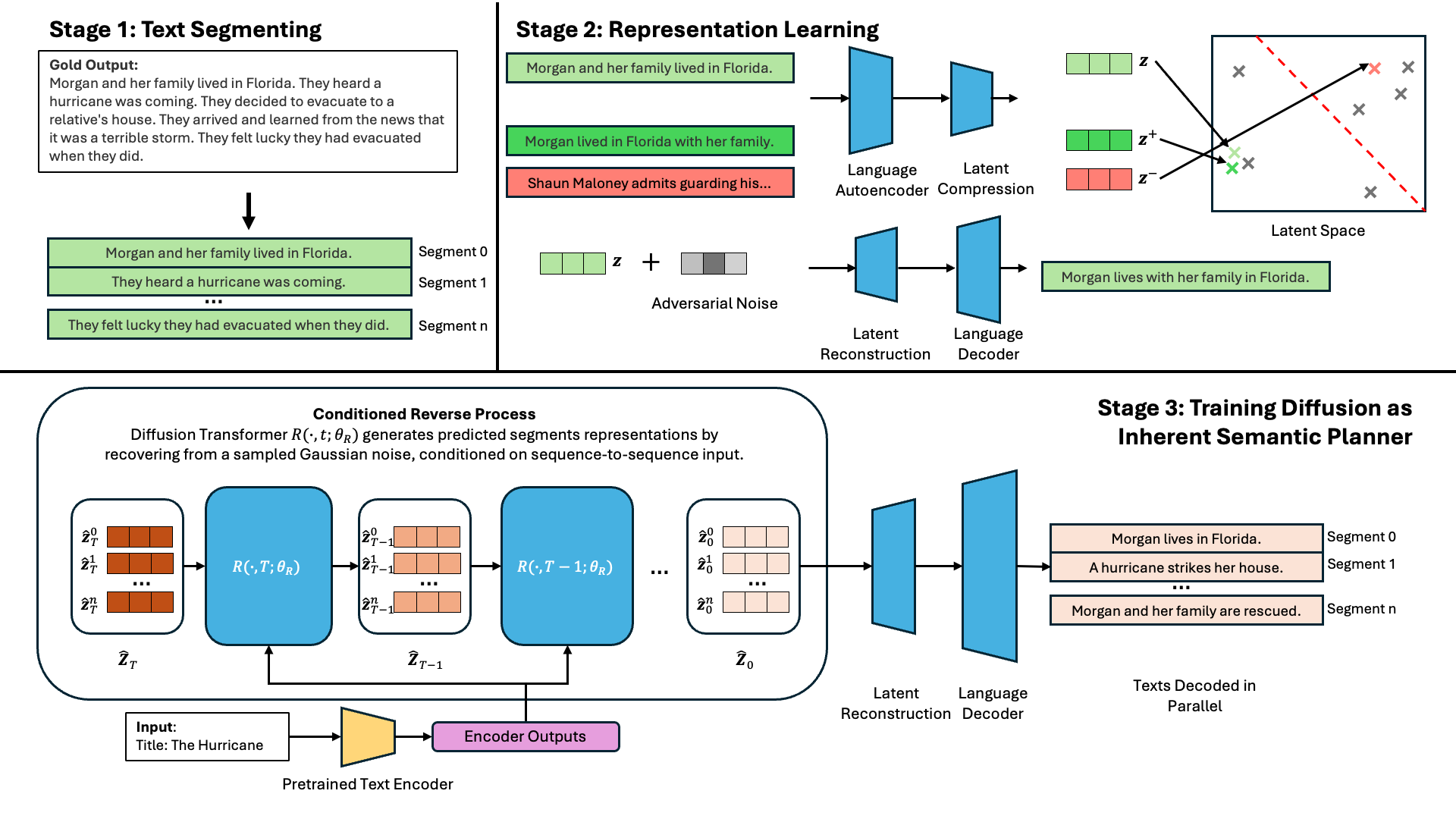

Zhu et al., 2024 (yeah that’s me 🤪) proposes Segment-Level Diffusion (SLD). Inspired by the concept of patching in image generation, we “patch” the text into coherent segments — like individual sentences, dialogue turns, or utterances. This gives us much better control over both the length of each segment and the semantic scope of each latent representation.

We further regularise the latent representations by doing additional training for representation learning, using contrastive learning, and adversial noise preturbation, ensuring local and distributional smoothness.

These tricks ensure both local and distributional smoothness, just like we talked about earlier. The diffusion model then learns to predict multiple latent representations, with one-to-one correspondence to each segment. Each segment’s latent can then be decoded independently — and in parallel! That means better generation quality and (maybe) faster inference (in theory, we will talk about this in the end). 💨

As demonstrate in the figure above, our SLD pipeline contains three major components, segmentation, representation learning and diffusion LM training. Blue units are trainable neural networks. On the top left, a paragraph of desired output text, the storylines, are segmented into sentences. These sentences are encoded and projected to a compact latent space. To further regularise the latent representation, as shown in top right, we do contrastive learning. We generate paraphrases as positive samples pulling them together, and randomly sample out-of-domain text as negative samples pushing them apart. In addition, we add some adversarial (worst case) noise to perturb the representations, training decoding units to be more robust. The bottom part describes the diffusion model training, we use cross-attention transformer conditioning on inputs and ensures 1-to-1 correspondence between latent representations and sentences over this process. The representations of all segments are decoded in-parallel in the end.

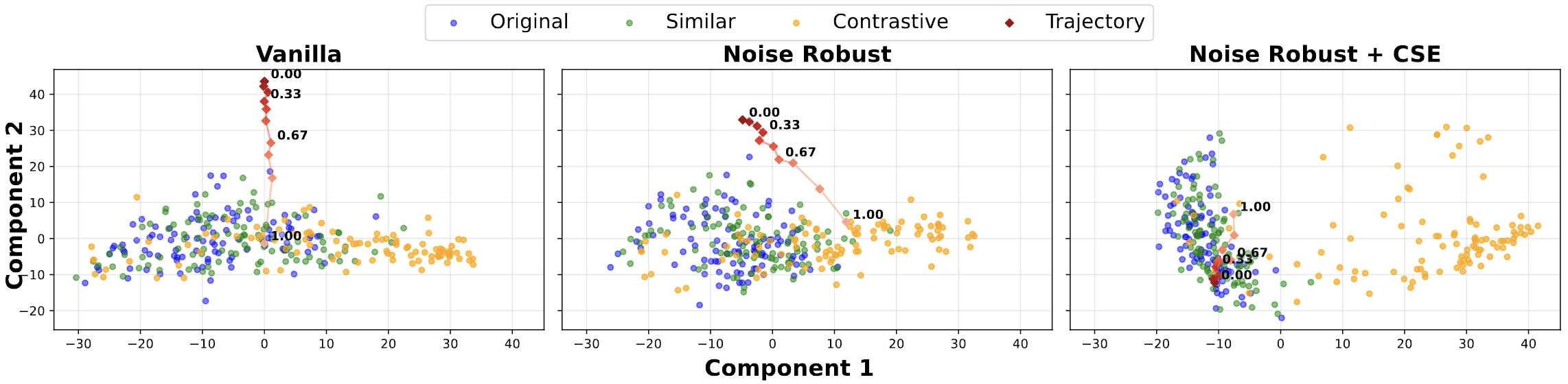

And you can see the importance of representation learning in the visualization below. Before the representation learning, the desired cluster of sentences (ROCStories) are not very distinguishable from other texts (CNN/Daily Mail), which makes the model susceptible to abrupt semantic changes during diffusion process. With regularization, it’s much better. Adversial noise is to ensure we enhance the generation quality even better.

A contemporaneous work from Meta, Large Concept Model, uses a similar paradigm. They perform diffusion over concepts — which is pretty much the same idea as segments in my work. Definitely check out their paper! They provide a model pre-trained on way more data than I had access to. In their work, they use a multimodal and multilingual encoder SONAR (definitely more powerful than the Flan-T5 encoder we were using) to generate concept embeddings.

Discrete Diffusion over Tokens

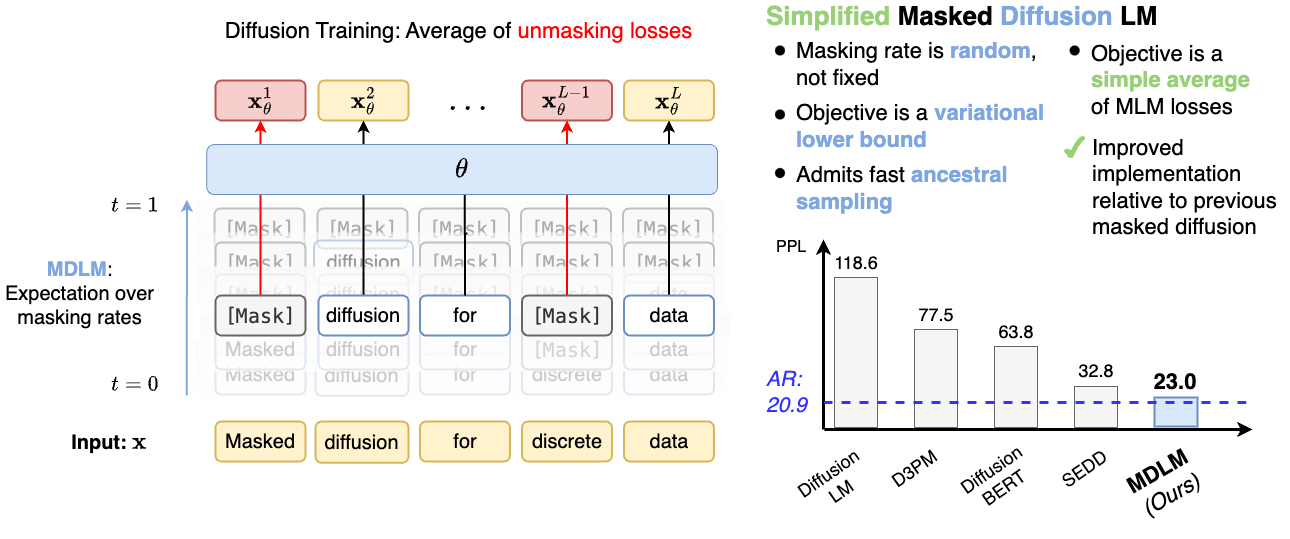

In this section, we’ll dive into how diffusion over discrete tokens is done — focusing on the Masked Diffusion Model (MDM) as introduced by Sahoo et al. in Masked Diffusion Language Models.

This will be our main example, but I also encourage you to check out:

However, fair warning: both are a bit mathematically dense and terse for a light intro blog like this one — so we’ll keep things digestible here. 🫠

D3PM introduces a Markov forward process over tokens, using a sequence of categorical distributions constructed through multiplication of transition matrices \(\mathbf{Q}_t\) across \(T\) discrete timesteps. Concretely, we have a series of matrix multiplications:

\[\begin{equation} \mathbf{x}_T = \mathbf{Q}_{T-1} \cdot \mathbf{Q}_{T-2} \cdots \mathbf{Q}_1 \cdot \mathbf{x}_0 \end{equation}\]This gradually transforms the initial sequence \(\mathbf{x}_0\) into a stationary distribution — i.e., full corruption.

In their work, tokens are represented as: \(\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{V}\) where \(\mathcal{V}\) is the set of all one-hot vectors of the vocabulary, and \(|\mathcal{V}| = K\).

They define \(\text{Cat}(\cdot; \boldsymbol{\pi})\) as a categorical distribution over \(K\) token classes, with class probabilities given by \(\boldsymbol{\pi} \in \Delta^K\) — the K-simplex (i.e., the space of valid probability vectors over \(K\) classes). They also define a special [MASK] token: \(\mathbf{m} \in \mathcal{V}\)

During the forward process, they interpolate discrete diffusion by gradually converting \(\mathbf{x}\) into increasingly noisy variables \(\mathbf{z}_t\). The marginal distribution of \(\mathbf{z}_t\) conditioned on the original \(\mathbf{x}\) is:

\[\begin{equation} q(\mathbf{z}_t \mid \mathbf{x}) = \text{Cat}(\mathbf{z}_t; \alpha_t \mathbf{x} + (1 - \alpha_t)\boldsymbol{\pi}) \end{equation}\]Here, \(\alpha_t\) is a scalar from the noise schedule, just like in standard diffusion models.

In the Sahoo et al.’s masked diffusion variant, they set: \(\boldsymbol{\pi} = \mathbf{m}\)

This means that at each timestep \(t\), the input token \(\mathbf{x}\) has a chance of being replaced by the special [MASK] token \(\mathbf{m}\). Once a token is masked — i.e., it transitions to \(\mathbf{m}\) at some time \(t\) — it stays masked for all subsequent timesteps. 🫥 (No going back from [MASK] — it’s a one-way trip.)

So, consequently, for the reverse diffusion process, we train a network to do \(p_{\theta} (\mathbf{z}_s | \mathbf{z}_t)\) to convert masked tokens back to concrete tokens.

\[\begin{equation} p_\theta(\mathbf{z}_s \mid \mathbf{z}_t) = q(\mathbf{z}_s \mid \mathbf{z}_t, \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{x}_\theta(\mathbf{z}_t, t)) = \begin{cases} \text{Cat}(\mathbf{z}_s; \mathbf{z}_t), & \mathbf{z}_t \neq \mathbf{m}, \\ \text{Cat}\left(\mathbf{z}_s; \frac{(1 - \alpha_s)\mathbf{m} + (\alpha_s - \alpha_t)\mathbf{x}_\theta(\mathbf{z}_t, t)}{1 - \alpha_t} \right), & \mathbf{z}_t = \mathbf{m}. \end{cases} \end{equation}\]Great, right? In this case, they’ve successfully extended diffusion from the continuous into the discrete domain. 🎉 I’ve omitted a few technical details — but you can check those out in their excellent blog or the full paper.

That said, note that the current design has some limitations. One issue is during decoding: Once a token is unmasked, it stays fixed. This isn’t ideal — especially in the early stages of reverse diffusion, when the paragraph is still mostly noise and the few decoded tokens are likely not optimal. But since they’re locked in place, the model must condition future generations on possibly bad guesses — causing the dreaded error propagation problem all over again. 😞

Lin et al., from Lingpeng Kong’s group (I really like their work!) propose a fix for this using a routing mechanism. The idea? Even during decoding, a previously decoded token can be remasked (i.e., turned back into [MASK]) if the model’s confidence in that token is low. This allows the model to revisit and revise its decisions — bringing in a form of iterative refinement that’s more faithful to the spirit of diffusion.

Finally, LLaDA 8B combines both techniques mentioned above — Masked Diffusion Language Modeling (MDLM) and routing — demonstrating the real potential of MDM as a new paradigm for pre-trained language models. The results? LLaDA achieves on-par — and in some cases superior — generation quality compared to autoregressive LLMs of the same size. Amazing, isn’t it? 🤯

Try it out yourself!

Text-in-Image Diffusion? (Brain-teaser)

Think computer vision for a moment! 👀 These days, NLP and CV have been borrowing ideas from each other all the time — just look at Tian et al., 2024’s VAR, which brings autoregressive generation into image synthesis. So hey, if we’re already using diffusion (the most trending paradigm in CV), why not push the crossover even further? I’ll skip over some amazing CV works like DeepFloyd IF for the sake of conciseness. Instead, here’s a fun little brain-teaser to wrap things up: GlyphDiffusion.

The key idea is wild but clever:

- Render the target text as a glyph image — that is, an actual visual representation of the characters —

- and treat conditional text generation as a glyph image generation task.

Now that you’re working in the image domain, you can naturally apply all your favorite continuous diffusion tricks — no discrete token rounding or masking needed! Let’s not worry (yet) about whether this is scalable or practical. At the very least… it’s fun. 😄

Challenges and Opportunities

You might be wondering:

“Hey, after reading through this blog, DLMs sound pretty well-established — we’ve even got pre-trained models already! So what’s stopping us from using them more widely?”

Great question. The short answer? Speed.

The major challenge for DLMs right now is inference efficiency and sampling cost. Yes, we’ve talked about how non-autoregressive (NAR) generation could potentially be faster than traditional AR methods — but… we’re not quite there yet. Autoregressive models have tricks like KV caching, which significantly boost decoding speed. Unfortunately, these acceleration methods aren’t applicable (yet) for NAR models like DLMs. Right now, naive DLM implementations are about 50× slower than AR baselines. 🐢

But! Don’t be discouraged — we’re making steady progress. There’s growing work adapting acceleration techniques to the diffusion domain, including:

- Consistency Models (OpenAI)

- Adaptive Decay Sampling (Tang et al., 2023)

- Diffusion of Thoughts (Ye et al., 2024), where they use ODE solvers to speed up decoding

And hey, some people have already pulled it off! Check out Inception Labs’ Mercury Coder — the first fast commercial DLM out in the wild!

But speed isn’t everything. There are so many opportunities with DLMs that we’ve only just begun to explore:

-

Since DLMs generate entire sequences holistically, could this change how we do reasoning?

Maybe it helps avoid bad intermediate steps and gives better chain-of-thought answers.

See: Diffusion-of-Thought, Dream 7B -

DLMs are great at fine-grained control, like in-filling, making them ideal for generating structured outputs with constraints:

tables, code, logical forms, and more.

Check out: TabDiff, Mario et al., 2024 -

The stochasticity of diffusion makes it a natural fit for data augmentation — especially useful for low-resource settings. Chen et al., 2024 used it to improve low-resource sentiment classification.

-

We can also think about how would this change the uncertainty estimation? As you can do sampling more naturally, maybe shed lights on self-consistency and other confidence related decoding (remasking).

-

And of course… multi-modal dreams!

Can we use one model to generate images and text together?

Meta’s Transfusion is already showing promising results.Though… technically they use AR for both images annd text.

So when we are doing this the other way around, maybe we should rename it: FusionTrans™ or DiffFormer™ 😎

Oh — and if you’re curious to keep up with this fast-growing area, shout out to the people who keep up-to-date list of all known DLM papers on GitHub. Highly recommended if you want to go down the rabbit hole. 🐇📚

Epilogue

I’ll end this introductory blog without a conclusion — because the Era of DLM has only just begun. 🚀

I hope this blog helped you understand DLMs a little better, and maybe even sparked some ideas if you’re thinking about doing DLM-related research yourself! (Oh gosh, I hope I didn’t make too many dad jokes or use too many emojis. 😅) If you liked this post, I might write more blogs in the future to dive deeper into specific aspects.

If you found this blog helpful and want to do me a favour, you can cite my Segment-Level Diffusion paper — I’ve incorporated most of this blog’s content into the related work section there. Also, feel free to leave a comment if you have any suggestions for improving the blog. I’d love to hear from you! 🙏

Until next time…

@misc{zhu2025segmentleveldiffusionframeworkcontrollable,

title={Segment-Level Diffusion: A Framework for Controllable Long-Form Generation with Diffusion Language Models},

author={Xiaochen Zhu and Georgi Karadzhov and Chenxi Whitehouse and Andreas Vlachos},

year={2025},

eprint={2412.11333},

archivePrefix={arXiv},

primaryClass={cs.CL},

url={https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.11333},

}

Update 24/05/2025

- Check out Gemini Diffusion Model! Seems like this field is getting more and more attention!

- Our paper Segment-Level Diffusion got accepted into ACL 2025 Main! See you in Vienna if you want to ask me anything!

- Special thanks to my amazing supervisor Prof. Andreas Vlachos for helping me in the project, and proof reading this blog. Shout out to my lab mates Suchir and Zeb for encouraging me writing this blog.